The year is 1923 and the American Radiator Company want to build a new office in New York. What will it look like? This was the Golden Age of Skyscrapers: the Woolworth Building was just ten years old, and the Empire State and Chrysler were both less then a decade away. So a skyscraper it had to be… but what sort of skyscraper?

Enter an architect called Raymond Hood, whose very first major project had been the still-uncompleted Tribune Tower in Chicago. Such was its reception that he was asked by the American Radiator Company to design their new headquarters. For them, working alongside his colleague J. André Fouilhoux, he produced something extraordinary. It was partly inspired by an architect called Eliel Saarinen, who had finished in second place in that competition (which Hood had won) to design Chicago’s Tribune Tower. You can see the similarities between Saarinen’s Neo-Gothic design and Hood’s American Radiator Building:

|

Where to begin? First: this was a masterpiece of colour. Obvious enough when you look at it — surprising, perhaps, that so few towers have embraced a similarly bold polychromy. The effect of using black bricks contrasted with gilded decorations (made with bronze paint) is startling. If a colour combination could exude grandeur it would surely be this. The crown of the building — a sort of fantastical nest of golden pinnacles — is particularly impressive. Hood believed New York’s skyscrapers had become too monotonous, and this was the reason for his embrace of colour. He hoped it would inspire a more technicolour design trend in general; it didn’t, but this very fact makes the American Radiator Building even more memorable.

|

These polychromatic, decorative motifs are also present at street level, where we see a Pseudo-Gothic portal, lined by niches and buttress, beneath a golden cornice and row of gilded grotesques:

|

It has been said that Hood broke with tradition in order to design the American Radiator Building. That is true, but only up to a point. Creating an engaged, detailed, decorated facade at pedestrian-level, and combining it with a many-pinnacled tower, was well within the models of time-honoured architectural tradition. It was rather in the design of its details where Hood’s thrilling modernity is revealed. Here we see the familiar forms of traditional architecture transformed into something rather more machine-like — especially in that soaring, angular, metallic crown. This, and the ornaments on the building’s facade, are perfect symbols of that strange decade, the simultaneously optimistic and apocalyptic 1920s, that still feel futuristic and (fundamentally) exciting even a century later. Of course, this style now has a name: Art Deco.

|

The American Radiator Building was also an exemplar of “Architecture of the Night”. This is a vague but useful term that refers, most broadly, to the way we illuminate buildings. To even consider this sort of thing was only possible thanks to the invention of powerful electrical lighting; though illumination is now a central part of architecture, in the 1920s it was a novel and yet-unmastered element of design. Well, Hood realised its potential and hired a Broadway designer to help him light up the American Radiator Building in the most effective way. He showed that illumination was vital: done right it could render skyscrapers incredibly dramatic, emphasising their details and adding a conscious work of art to a city’s skyline.

|

Finally, we need to mention the building’s overall form. See, after the construction of the Equitable Building in 1915 — which rose a full forty storeys sheer from the sidewalk — the 1916 New York Zoning Resolution was introduced. This required buildings to have “setbacks”, meaning that the upper storeys had to be further back than the lower storeys, in order to let light and air reach street level. This presented a challenge for architects, but the question of how to adapt skyscrapers to the Zoning Resolution was successfully answered by a poet-draughtsman-visionary called Hugh Ferriss. In 1922 he published a set of influential drawings showing how setbacks might be designed, and insodoing created the definitive Art Deco skyscraper model in one fell swoop:

|

Ferriss actually worked with Hood on the American Radiator Building, and helped him visualise what it might look like when completed. Thus Hood and Ferriss together created the first true Art Deco skyscraper, complete with its iconic “waterfalls” of masonry, to be emulated time and again around the world. Rather than being treated as ordinary buildings elongated upwards, skyscrapers would now be designed like colossal sculptures with huge, visually appealing silhouettes.

So what the American Radiator Building represents, above all, is a thrilling moment of metamorphosis, squeezed into a decade-long transition from the Old Architecture to the New Architecture. Around the late 19th and early 20th centuries a series of new inventions — reinforced concrete, steel, electricity, power tools, plate glass — allowed for buildings of a scale and form previously impossible. But, before a style uniquely suited to those technologies and materials — our unornamented, streamlined, glass towers, or what we might loosely call “Modernism” — had been fully crafted, it was the old style, built on centuries of slow development, that still held sway. Hence the Neo-Gothic and the Neo-Classical skyscrapers of the early decades of the 20th century. And it was here, just as things were beginning to shift, that Art Deco emerged, defined by its mixture of setback towers (creating, as stated, those “waterfalls” of masonry and glass), opulent materials, and futuristic decorations.

If you compare the crown of the Tribune Tower, which was more traditional Gothic, to the crown of the American Radiator Building, you can see this transition most clearly. On the right-hand side I have also included the pinnacle of the McGraw-Hill Building, also designed by Hood and much plainer, much closer to the Modernism that would conquer the world in the 1950s. So much happened, stylistically, in a single decade — and you can see that transformation playing out in these three towers by Hood.

|

Hood, after the American Radiator Building, would go on to design other major towers like the aforementioned McGraw-Hill Building, the Daily News Building, and the Rockefeller Center — all of them now iconic, all supreme achievements of various kinds of Art Deco. But the American Radiator, surely, was his magnum opus. And to end I should mention that, should any of you be in London, then you may wish to visit a most curious place in Soho. It was called Ideal House, now Palladium House, and was designed by Raymond Hood himself as a sort of miniature version of the American Radiator Building — with black bricks and gold decoration, though this time Pseudo-Egyptian rather than Pseudo-Gothic — in 1929.

|

Risorsa: The Cultural Tutor

![]() | | Pubblica

| | Pubblica

Seleziona una delle attività più popolari qui sotto oppure affina la ricerca.

Scopri gli itinerari più belli e popolari della zona, accuratamente raggruppati in apposite selezioni.

Risorsa: The Cultural Tutor

Seleziona una delle categorie più popolari qui sotto o lasciati ispirare dalla nostra selezione.

Scopri i luoghi di interesse più belli e popolari della zona, accuratamente raggruppati in apposite selezioni.

Risorsa: The Cultural Tutor

Con RouteYou puoi creare facilmente mappe personalizzate. Traccia il tuo itinerario, aggiungi waypoint o nodi, luoghi di interesse e di ristoro, e condividi le mappe con la tua famiglia e i tuoi amici.

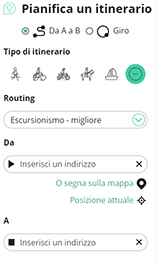

Pianificatore di itinerari

<iframe src="https://plugin.routeyou.com/poiviewer/free/?language=it&params.poi.id=9023644&params.language=en" width="100%" height="600" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

© 2006-2025 RouteYou - www.routeyou.com